Unpacking the Extraordinary Science of Junk Food: A Journey from Childhood Lunches to Sensory Satiety

The intricate world of food science, particularly as it pertains to highly processed and often addictive junk foods, is a topic that continues to fascinate and, at times, alarm. It delves deep into human psychology, biology, and the cunning strategies employed by the food industry. A truly captivating piece that explored this very subject was published by the New York Times: “The Extraordinary Science of Addictive Junk Food.” This article, which I wholeheartedly recommend, offers a profound look into how food enterprises engineer products that are not just palatable, but almost irresistibly compelling. Its discussion of the “sensory-specific satiety” principle, in particular, resonated deeply and offered a scientific lens through which to view some of my own childhood food experiences, including the infamous Lunchable box.

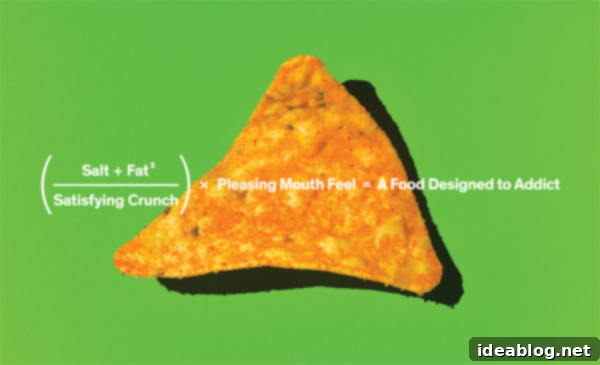

At its core, “sensory-specific satiety” describes a phenomenon where the pleasure derived from eating a particular food decreases as you consume more of it, while the desire for other, different foods remains strong. Imagine eating a plate of pasta; after a few bites, your craving for pasta might wane, but you could still be tempted by a side salad, a piece of bread, or a dessert. Food companies, armed with this knowledge, design products that either offer multiple, distinct sensory experiences within one serving or manipulate individual sensory aspects (like taste, texture, and aroma) to delay or circumvent this satiety. The goal is simple: encourage consumers to eat more, driving incredible profitability and success for items like sugary cereals, salty snacks, and those compartmentalized lunch kits that once dominated school cafeterias.

This scientific manipulation explains how various food enterprises have managed to create incredibly profitable and widely successful food products. They understand the “bliss point”—the perfect amount of sugar, salt, or fat that makes a food maximally enjoyable—and how to combine textures and flavors to create an experience that keeps you reaching for more. The Lunchable, for instance, is a masterclass in this. It offers multiple components – a cracker, a slice of “ham” or “turkey,” and a piece of processed cheese – each providing a slightly different texture and flavor profile, preventing the consumer from quickly experiencing sensory fatigue. This ingenious design, whether consciously or unconsciously appreciated by its target demographic, made it a school lunch staple and an object of intense desire for many children, myself included.

Thinking back to my own school days, my mom was a diligent lunch packer (and for that, I am eternally grateful, mom!). Unlike many of my peers who flaunted their store-bought, pre-packaged meals, my favorite packed lunch was a bit more artisanal, if I can say so myself. It typically consisted of plain pasta, generously topped with freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese – a simple yet incredibly satisfying dish. Alongside this, I’d have a serving of unsweetened applesauce, a refreshing box of Tropicana grapefruit juice, and if I was particularly lucky, a coveted fruit snack like Gushers, Shark Bites, or Fruit by the Foot. I was utterly obsessed with all fruit snacks; their vibrant colors, artificial fruit flavors, and unique textures provided that specific burst of joy that only a child’s palate can fully appreciate.

Meanwhile, as I savored my homemade pasta, my friends around me would be enthusiastically breaking out their Lunchables and Dunkaroos. Oh, the sheer envy! At the time, I was incredibly jealous and genuinely believed that these pre-packaged marvels were the epitome of culinary cool. There was an undeniable allure to their convenient, self-contained nature and the implicit promise of fun they carried. After much persistent pleading, I believe I was eventually able to convince my mom to finally buy me *one* Lunchable. And not just any Lunchable; I sidestepped the rather questionable ham, cheese, and cracker variety that was so common, opting instead for the “DIY-Pizza” version. That was totally more my style, offering a glimmer of creative culinary freedom within a pre-portioned package. Talk about thrilling anticipation!

The experience, however, was a stark lesson in the difference between perception and reality. Spreading what was essentially a sweetened tomato paste onto a soft, spongy “pizza crust” and then loading it with an un-melted, rubbery disk of processed cheese was, in theory, sort of fun. Heck, you got to play with your food, which is probably every elementary school teacher’s worst nightmare, yet every child’s dream! But the taste? It was, to be quite honest, pretty revolting. The artificial flavors, the strange texture combinations, and the general lack of freshness were an immediate turn-off. I realized, almost instantaneously, that my own packed lunches, humble and perhaps less “cool” as they might have seemed, were *far* superior in taste and overall satisfaction. In fact, if I were packed that very same pasta, Parmigiano, and fruit snack lunch up to this day, I’d be a pretty happy camper. It speaks volumes about the enduring appeal of simple, quality ingredients over engineered convenience.

This personal anecdote, though seemingly trivial, perfectly illustrates the profound impact of food science. While the Lunchable excelled in novelty, convenience, and a certain playful element that captivated children, its actual taste profile couldn’t compete with the wholesome, flavorful ingredients my mother carefully prepared. The “extraordinary science” of junk food doesn’t necessarily create *better tasting* food in a traditional sense, but rather food that triggers specific reward pathways in the brain, making it highly desirable and often difficult to resist. The initial thrill of the DIY pizza faded quickly once the artificiality of its components became apparent. It was a fascinating, albeit disappointing, encounter with a highly engineered food product that promised much more than it delivered in terms of genuine culinary pleasure.

The broader implications of this science extend beyond childhood memories and school lunchboxes. The constant exposure to foods engineered for maximal “bliss points” and sensory diversity can subtly reshape our palates, making less intensely flavored natural foods seem bland in comparison. This can contribute to unhealthy eating habits and a preference for ultra-processed items over fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Understanding sensory-specific satiety and other food industry tactics empowers us as consumers to make more informed choices, distinguishing between fleeting novelty and truly satisfying, nourishing food experiences. It reminds us that while convenience and clever marketing can be powerful, genuine taste and quality ingredients often provide the most enduring pleasure and satiety.

Ultimately, my brief venture into the world of Lunchables taught me a valuable lesson about the allure of marketing versus the reality of taste. It also fostered a deeper appreciation for the effort my mother put into our meals, ensuring they were not only nutritious but genuinely delicious. It’s a testament to how even the simplest homemade meals can outperform the most scientifically engineered “fun” foods. As we navigate a world increasingly dominated by processed foods, perhaps a return to the fundamentals of good, simple cooking—and an understanding of the science behind what we eat—is more important than ever.

What was in your school lunchbox? Share your nostalgic food memories and perhaps even your own tales of junk food envy or disappointment!

(Image Source: Grant Cornett for the New York Times)